The first hint that anything was amiss was a robbery on a Saturday afternoon in 1969 at the headquarters of the National Committee Against Repressive Legislation (NCARL) in Los Angeles.

Four armed men, alternately speaking Spanish and English, locked a frightened office worker in the bathroom and ordered the building watchman to lie down under a rug, threatening to “blow his brains out” if he did not.

The men then burst through the office door with a sledgehammer and scattered the contents of the files across a table top. The file marked “correspondence” disappeared.

At NCARL, an organization committed to seeing the House Committee on Un-American Activities abolished–and accustomed to trouble in an era when left-wing groups came under frequent attack–no one thought much about the robbery.

It wasn’t until four years later that NCARL officials began noticing similarities between their own robbery and a series of White House-directed political break-ins during the same period–in particular, the 1971 burglary of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office only a few miles away by a band of Cubans hired by Watergate conspirators G. Gordon Liddy and E. Howard Hunt.

NCARL’s executive director, Frank Wilkinson, wrote Watergate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox and demanded to know if there was a connection. There wasn’t, Cox wrote back, but Cox said he was nonetheless intrigued enough about the robbery to turn over Wilkinson’s letter to the FBI.

Thus began more than 10 years of inquiries and litigation that eventually convinced Wilkinson that the FBI, charged with investigating the robbery, had perhaps committed it.

A wave of documents that began flowing in from FBI offices all over the country revealed that Wilkinson had been a target of FBI surveillance for nearly 30 years.

Probed Further

His work promoting public housing in Los Angeles, his speeches at college campuses and service clubs, his conversations with friends, bank deposits–all had been documented, analyzed, assigned reference numbers and deposited in FBI files.

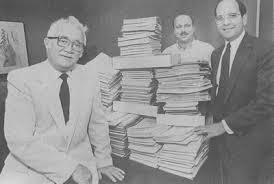

After Wilkinson’s initial inquiries, the FBI admitted that it had accumulated 4,500 pages of surveillance reports documenting the milestones of his life. Then, when Wilkinson probed further, the agency admitted it had as many as 12,000 pages.

Now, eight years after Wilkinson first filed suit for violation of his constitutional rights, the FBI has entered into a partial settlement under which it will turn over to the national archives up to 132,000 pages of surveillance documents on Wilkinson and his political activities.

The settlement, recently approved by U.S. District Judge A. Wallace Tashima, substantially concludes what many believe is the last major chapter in the FBI’s counterintelligence program, under which the government conducted a secret domestic spying campaign against a variety of U.S. organizations thought to be violent or subversive.![]()

Although there have been numerous lawsuits in the last decade challenging the controversial program that officially terminated in 1971, few have so clearly captured the essence of what has come to be known as the McCarthy Era in American politics.

Moreover, none have so firmly documented the close links that existed during those years between the FBI under former Director J. Edgar Hoover and the red-hunting House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Page by page, the files released so far document the FBI’s efforts to discredit Wilkinson, a Los Angeles community activist who became a national leader in the movement to abolish the House committee, by planting news stories about Wilkinson’s alleged communist affiliations, setting up counter-demonstrations at his public appearances and mailing anonymous “poison pen” letters to NCARL’s financial supporters.

One of First Convicted

The documents establish that the FBI knew the precise time and location of a planned assassination attempt against Wilkinson in 1964 and failed to warn him about it. (The FBI says it alerted local law enforcement authorities, but the threat was never carried out.)

And when Wilkinson became one of the first to be convicted of contempt of Congress for refusing to answer the House committee’s questions about his political affiliations, the files show that the FBI contacted an undisclosed source in the office of the U.S. Supreme Court about the progress of his case–raising questions about the agency’s influence on the nation’s highest court.

“I think this case is very unusual in terms of the size of the file and the intensity of the surveillance, and the apparent personal interest that Hoover and high-level FBI agents had in Frank’s activities is really quite unusual,” said Paul Hoffman, legal director for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, which, with the law firm of Loeb & Loeb (working on a pro bono basis), represented NCARL in the FBI litigation.